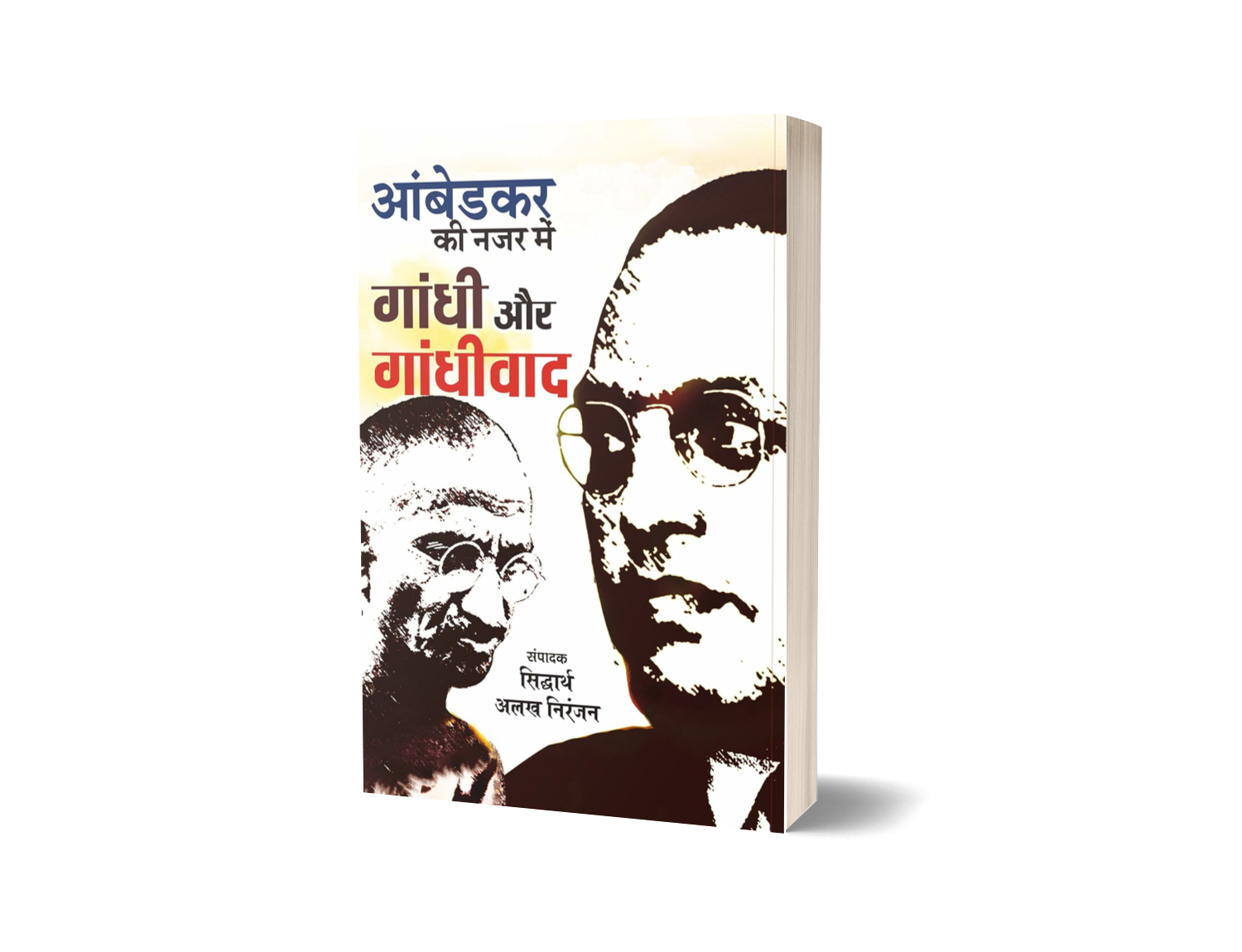

AMBEDKAR KI NAJAR MEIN GANDHI AUR GANDHIVAAD

- Binding: Paperback

- Language: Hindi

Original price was: ₹200.00.₹195.00Current price is: ₹195.00. /-

5 in stock

Order AMBEDKAR KI NAJAR MEIN GANDHI AUR GANDHIVAAD On WhatsApp

Description

AMBEDKAR KI NAJAR MEIN GANDHI AUR GANDHIVAAD

Ambedkar Ki Nazar Mein Gandhi Aur Gandhivaad: A Deep Dive into Ideological Conflict

Ambedkar Ki Najar Mein Gandhi Aur Gandhivaad is a seminal book authored by Siddharth and Alakh Niranjan that explores the ideological, political, and philosophical differences between two towering figures of modern India, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar and Mahatma Gandhi.

This book goes beyond simplistic interpretations of their interactions and provides a nuanced critique of Gandhi and his philosophy, Gandhism, from Ambedkar’s perspective. It delves into the ideological chasm that separated these two leaders, especially regarding caste, untouchability, religion, and approaches to India’s socio-political problems.

The book is a rich commentary on the era of India’s freedom struggle and sheds light on the intellectual debates that shaped the course of Indian history. It provides readers with a deeper understanding of Ambedkar’s thought process and how his critique of Gandhi and Gandhism was rooted in his vision of a just, equitable, and caste-free society.

Ambedkar’s Perspective on Gandhi and Gandhism

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, one of the most prominent leaders of the Dalit community in India and a social reformer, had a complex and critical view of Mahatma Gandhi and his ideology of Gandhism. Ambedkar, a staunch advocate for social justice and equality, disagreed with Gandhi’s methods and philosophy on several fronts. His criticism of Gandhi was not only rooted in personal differences but also in the fundamental disagreement over their approaches to caste, the role of religion in social reform, and the future of India’s social order.

differences but also in the fundamental disagreement over their approaches to caste, the role of religion in social reform, and the future of India’s social order.

1. Gandhi’s Attitude Towards the Caste System

Ambedkar’s most significant criticism of Gandhi was centered on the issue of caste. Gandhi, though deeply concerned with the welfare of the lower castes, particularly the “Untouchables,” whom he called “Harijans” (children of God), did not challenge the caste system itself. Gandhi’s approach was based on moral reform and humanitarian efforts to uplift the lower castes, but he accepted the varna system as a part of Hindu tradition.

For Ambedkar, however, the caste system was not just a social issue; it was a deeply entrenched system of oppression that required systemic reform. Ambedkar argued that the caste system was the root cause of the marginalization of Dalits and that Gandhi’s attempts to improve the condition of the lower castes were insufficient.

While Gandhi focused on the reform of the individual, Ambedkar advocated for legal, constitutional, and institutional changes to dismantle the caste system entirely.

Ambedkar was particularly critical of Gandhi’s insistence on using Hindu religious texts like the Bhagavad Gita to promote social reform. Ambedkar believed that these texts were inherently discriminatory against Dalits and other marginalized groups. He argued that Gandhi, despite his good intentions, was perpetuating the Hindu social order, which kept the Dalits at the bottom of the social hierarchy.

2. The Poona Pact: A Critical Turning Point

The Poona Pact, signed in 1932, was a watershed moment in the relationship between Gandhi and Ambedkar. The pact was an agreement between the British colonial government, Gandhi, and Ambedkar over the issue of separate electorates for the Untouchables. Gandhi, who was firmly against separate electorates for Dalits, began a fast unto death to protest the British decision to give them political autonomy through separate electorates.

Ambedkar, representing the Dalit community, saw separate electorates as a means of ensuring political representation for his people. He believed that without separate representation, the Dalits would remain politically marginalized and their interests would continue to be ignored in the broader Hindu-majority political landscape. On the other hand, Gandhi, who was committed to Hindu unity, believed that separate electorates would divide the Hindu community and weaken the fight for India’s independence from British rule.

The pressure of Gandhi’s fast ultimately led to the Poona Pact, which provided for joint electorates but with reserved seats for the Dalits. While Ambedkar accepted the pact to avoid Gandhi’s death, he was deeply disappointed by the compromise. He felt that the pact did not go far enough in ensuring the political empowerment of Dalits and that it was a victory for Gandhi’s vision of a unified Hindu society, which excluded the interests of the Dalit community.

3. Gandhi’s Religion and Ambedkar’s Rationalism

Another point of contention between Gandhi and Ambedkar was their respective attitudes towards religion. Gandhi was a devout Hindu who believed that his political and social ideas were rooted in the values of Hinduism.

He emphasized the importance of religious tolerance, non-violence (ahimsa), and truth (satyagraha) as guiding principles for both personal and societal transformation. Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence was central to his approach to political resistance, and he saw Hinduism as a moral guide for his activism.

Ambedkar, on the other hand, was a rationalist and a critic of organized religion. He believed that religion, particularly Hinduism, was an instrument of oppression and that it reinforced the caste system.

Ambedkar’s view of religion was pragmatic; he advocated for a religion that could offer liberation and equality for all, especially the marginalized. His rejection of Hinduism culminated in his conversion to Buddhism in 1956, a move that symbolized his break from the oppressive structures of Hinduism.

Ambedkar’s rejection of Gandhi’s religiously grounded approach to social reform was rooted in his belief that religion, rather than being a source of liberation, was a tool of the ruling class to maintain the status quo. Gandhi’s reliance on religious discourse, in Ambedkar’s view, prevented him from fully understanding the socio-political dimensions of the Dalit struggle and hindered any substantial challenge to the caste system.

4. The Political Question: Nationalism and Hindu Unity

Both Gandhi and Ambedkar were deeply involved in the struggle for India’s independence from British colonial rule, but their approaches to nationalism differed significantly. Gandhi’s concept of nationalism was based on the unity of all Hindus, regardless of caste, and he believed that the struggle for independence could only be successful if all Hindus, including the lower castes, united under the banner of Hinduism.

of caste, and he believed that the struggle for independence could only be successful if all Hindus, including the lower castes, united under the banner of Hinduism.

Ambedkar, however, had a more inclusive and secular vision of nationalism. While he was committed to the goal of Indian independence, he believed that the upliftment of the Dalits could not be subordinated to the cause of Hindu unity.

Ambedkar feared that the independence movement, led by leaders like Gandhi, would simply replace British rule with a new form of Brahminical domination. He argued that India’s independence would be meaningless unless the Dalits were granted true equality, not just politically but socially and economically as well.

Ambedkar’s vision of nationalism was based on the ideals of justice, equality, and liberty for all, irrespective of their caste or religion. He advocated for a constitutional guarantee of these rights, something that Gandhi, who remained deeply committed to the idea of Hindu unity, did not fully embrace.

5. Ambedkar’s Disillusionment and the Break from Gandhi

Over time, Ambedkar became increasingly disillusioned with Gandhi and his approach to social reform. He saw Gandhi’s idealism and religious philosophy as a barrier to real change for the Dalit community. Gandhi’s refusal to take strong, concrete steps to challenge the caste system, his emphasis on individual moral reform over structural change, and his prioritization of Hindu unity over social justice were central to Ambedkar’s growing frustration with him.

In his writings, particularly in his book Thoughts on Linguistic States and in his speeches, Ambedkar was scathing in his critique of Gandhi. He saw Gandhi as a leader who, despite his humanitarian efforts, failed to recognize the deep-rooted social injustices that Dalits faced in Hindu society. Ambedkar believed that Gandhi’s approach only served to placate the Dalits without addressing the underlying causes of their suffering.

6. Ambedkar’s Legacy and Critique of Gandhi’s Philosophy

Despite their differences, Ambedkar and Gandhi shared a common goal: the improvement of the condition of the marginalized in India. However, their methods, philosophies, and understanding of the caste system diverged significantly. Ambedkar’s legacy is one of radical social change, grounded in legal and political reforms, while Gandhi’s legacy is rooted in non-violent resistance and moral upliftment.

Ambedkar’s critique of Gandhi and Gandhism is not just about personal disagreements; it is a profound disagreement over the nature of social change in India. Gandhi’s vision was one of gradual, moral reform, while Ambedkar’s vision was one of radical, structural transformation.

Ambedkar believed that true social justice could only be achieved through a complete overhaul of the caste system and by establishing a secular and egalitarian society. In contrast, Gandhi’s vision, though noble, often remained confined to the ideals of Hinduism and failed to address the deep-seated caste-based oppression that defined much of Indian society.

Conclusion

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s critique of Gandhi and Gandhism is an important part of the discourse on India’s independence and social reform. Ambedkar, as a leader of the Dalits, saw Gandhi’s approach as insufficient and often counterproductive to the cause of social justice.

His insistence on a complete break from the caste system, his secular vision of social change, and his emphasis on constitutional reforms set him apart from Gandhi’s moralistic and religious approach.

While both men contributed significantly to the freedom struggle, their differing views on caste, religion, and social justice have left a lasting impact on India’s political and  social landscape. Ambedkar’s vision of an egalitarian India, grounded in law and reason, remains an enduring legacy, offering a more radical and inclusive alternative to Gandhi’s idealism.

social landscape. Ambedkar’s vision of an egalitarian India, grounded in law and reason, remains an enduring legacy, offering a more radical and inclusive alternative to Gandhi’s idealism.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, a staunch critic of the caste system, viewed Gandhism as a philosophy that failed to adequately address the structural oppression of Dalits and other marginalized communities.

While Gandhi championed the abolition of untouchability, he upheld the Varna system, which Ambedkar saw as the root cause of caste-based discrimination. This foundational difference forms the core of the book, which outlines Ambedkar’s disagreements with Gandhi’s reformist stance and his vision of India’s socio-political future.

Ambedkar believed that Gandhi’s approach to the caste problem was rooted in maintaining Hindu orthodoxy. In contrast, he advocated for a complete annihilation of caste. The book explores how Ambedkar’s proposals, such as separate electorates for Dalits, clashed with Gandhi’s vision of an undivided Hindu society, leading to the famous Poona Pact of 1932.

Key Themes in the Book

1. Caste and Untouchability

The book critically examines the contrasting approaches of Ambedkar and Gandhi to caste and untouchability. Gandhi’s concept of Harijan upliftment, which he championed as a moral obligation of upper-caste Hindus, is juxtaposed with Ambedkar’s demand for social justice and political representation for Dalits.

Ambedkar criticized Gandhi’s patronizing approach, arguing that it perpetuated the subjugation of marginalized communities rather than empowering them.

Caste and untouchability are deeply rooted social phenomena in India, with a long and painful history. They are products of a complex system that has evolved over millennia and has had profound implications on the structure of society.

While caste continues to shape Indian society in numerous ways, untouchability represents the most extreme and abhorrent manifestation of this social stratification. Understanding the intricacies of caste and untouchability involves exploring their origins, development, societal consequences, and the ongoing struggle for justice and equality.

The Origins of Caste System

The roots of the caste system in India can be traced to ancient texts, particularly the Rigveda, where the division of labor is first recorded in the form of the four varnas: Brahmins (priests and scholars), Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), Vaishyas (merchants and landowners), and Shudras (laborers and servants).

This classification, however, was originally based on the division of labor rather than rigid social hierarchy. Over time, the system evolved and became more rigid, with the emergence of the concept of jatis, or sub-castes, leading to the complex caste hierarchy seen today.

The Manusmriti, an ancient Hindu law code attributed to the sage Manu, further institutionalized caste. This text codified the rules regarding caste duties and social roles, placing Brahmins at the top of the social order and Shudras at the bottom, with the untouchables (or Dalits) existing outside of this four-fold structure.

The Manusmriti and other religious texts such as the Bhagavad Gita and the Mahabharata laid the foundation for a social order that not only organized society but also justified the inherent inequality between castes.

Over centuries, this system became deeply entrenched in society. Caste was no longer just a social stratification based on occupation but evolved into a hereditary status, passed down from one generation to the next. This transformation led to the development of a rigid social order where the mobility between castes was severely restricted. Caste identity became an intrinsic part of an individual’s social, economic, and even spiritual life.

Untouchability: The Most Extreme Form of Caste Discrimination

Untouchability is a form of social exclusion and segregation that targets certain groups at the lowest levels of the caste system. These individuals, often referred to as Dalits, were historically considered “impure” or “polluted” and were subjected to the most severe forms of discrimination, marginalization, and violence.

Dalits were traditionally relegated to tasks considered “unclean” or “impure,” such as handling dead bodies, cleaning toilets, or working with animal hides. This led to the belief that contact with a Dalit could contaminate higher-caste individuals. Consequently, Dalits were socially and physically isolated from the rest of society. They were forced to live in separate settlements, denied access to public spaces like temples, wells, and schools, and were excluded from mainstream social, economic, and cultural life.

The concept of untouchability is not just a social practice but a deep-seated religious and cultural belief that has been perpetuated by various Hindu texts and practices. The belief in ritual purity and impurity reinforced the segregation of Dalits from the rest of society. Touching a Dalit, sharing food with them, or even being in their physical proximity was seen as polluting.

This belief system has had a lasting impact on the lives of millions of people and continues to affect social dynamics in modern India.

Legal and Political Developments: The Abolition of Untouchability

The fight against untouchability has been one of the central struggles in Indian history, particularly in the context of the Indian independence movement. Several key figures, most notably Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, played a crucial role in challenging the caste system and advocating for the rights of Dalits.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar was born into an untouchable family and faced severe discrimination throughout his life. His experiences with untouchability shaped his worldview and his commitment to social justice. Ambedkar argued that the caste system was incompatible with modern democratic principles and that it perpetuated systemic inequality, depriving Dalits of their fundamental rights. He famously said, “Caste is a system of graded inequality.”

Ambedkar’s efforts were instrumental in securing legal protections for Dalits in independent India. As the chairman of the drafting committee of the Indian Constitution, he ensured that the constitution abolished untouchability and granted equal rights to all citizens, irrespective of their caste or religion. Article 17 of the Indian Constitution, which prohibits untouchability, marked a historic step in the fight against caste-based discrimination.

However, while the legal abolition of untouchability was a significant achievement, the social and economic consequences of caste discrimination were far from over. Despite the constitutional ban, untouchability practices persisted in many parts of India, often in subtle or covert forms.

Caste and Its Manifestation in Contemporary India

Despite the legal protections afforded to Dalits, the caste system continues to be deeply ingrained in Indian society. The persistence of caste discrimination can be observed in several forms, including:

- Social Discrimination: Caste-based social discrimination remains prevalent in many rural areas and even in urban settings. Dalits often face exclusion from social gatherings, marriage alliances, and religious practices. In many regions, Dalits are still denied access to common resources like water sources, temples, and even roads. The practice of untouchability is still reported in certain areas, where Dalits are forced to use separate utensils in public spaces, are not allowed to enter certain buildings, or are not permitted to sit in the same area as higher-caste individuals.

- Economic Disparities: Economic inequality between castes remains a significant issue. Dalits, historically denied access to land and economic resources, continue to face higher levels of poverty and unemployment. Many Dalits are still engaged in menial labor, often in the form of manual scavenging, which remains a deeply stigmatized and dangerous profession.

- Although reservations (affirmative action policies) have been implemented to help Dalits gain access to education, employment, and political representation, these policies have faced significant opposition and have not entirely removed the systemic barriers to economic advancement.

- Violence and Atrocities: Dalits remain vulnerable to violence and exploitation. Attacks on Dalits, including physical assaults, rapes, and murders, continue to be reported, particularly in rural areas. The caste system’s deep roots in the social fabric of India have led to entrenched prejudices that manifest in horrific acts of violence against Dalits, often with impunity for the perpetrators.

- Political Manipulation of Caste: Caste politics has become a significant feature of Indian democracy, with political parties often catering to caste-based interests. While this has given Dalits a political voice, it has also perpetuated caste-based identities, making it difficult to transcend caste divisions. Political leaders may exploit caste identities for electoral gains, which in turn can reinforce the notion of caste-based inequality.

- Cultural Representations and Stereotypes: Caste-based stereotypes continue to be perpetuated through media, literature, and popular culture. Dalits are often portrayed as servile, submissive, or criminal, reinforcing negative stereotypes. These cultural representations contribute to the continued social stigma and marginalization of Dalits.

Ambedkar’s Vision for a Caste-Free Society

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar envisioned a society free from caste-based discrimination and untouchability. His approach to achieving this goal was both radical and pragmatic. Ambedkar believed that the caste system could not be reformed within the framework of Hinduism, as the religion itself perpetuated caste-based discrimination. His conversion to Buddhism in 1956 was a symbolic rejection of the Hindu caste system and an embrace of a more egalitarian religious philosophy.

rejection of the Hindu caste system and an embrace of a more egalitarian religious philosophy.

Ambedkar’s vision for a caste-free society was based on the principles of justice, equality, and fraternity. He believed that true social reform could only be achieved through a combination of legal, social, and economic measures. Ambedkar’s fight for the rights of Dalits was not just about uplifting them socially but about dismantling the very foundations of caste-based oppression.

He advocated for the creation of a secular, inclusive society, where individuals were valued for their capabilities rather than their caste origins. Ambedkar’s ideas laid the foundation for modern Dalit activism, and his advocacy for education, political representation, and social justice continues to inspire movements for caste abolition today.

Conclusion

The caste system and untouchability represent one of the darkest chapters in the history of India, and their legacy continues to shape the lives of millions of people. While significant progress has been made in terms of legal abolition and social reforms, caste-based discrimination remains a pervasive issue in Indian society. The continued struggle for justice and equality requires a multifaceted approach that includes legal reforms, social awareness, and economic empowerment for Dalits.

Ambedkar’s legacy reminds us that the fight against caste-based discrimination is not just a political or legal battle but a moral and social one. His vision for a caste-free society remains an enduring call for equality, justice, and dignity for all people, irrespective of their caste, religion, or background. Only through sustained efforts can the ideals of a truly egalitarian society be realized.

2. The Poona Pact and Its Aftermath

One of the most significant events discussed in the book is the Poona Pact of 1932, where Gandhi’s opposition to separate electorates for Dalits forced Ambedkar to compromise. The authors provide a detailed analysis of Ambedkar’s disillusionment with this outcome and how it shaped his future strategies for Dalit emancipation.

The Poona Pact, signed in 1932 between Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, is a pivotal moment in the history of India’s struggle for independence and social justice. It primarily addresses the issue of political representation for the marginalized sections of Indian society, particularly the Dalits (then referred to as the “untouchables”).

This agreement marked a significant turning point in the relationship between the Indian nationalist movement and the Dalit community and had lasting effects on India’s political and social landscape.

The Context Leading to the Poona Pact

In the early 20th century, India was undergoing a significant transformation. British colonial rule, which had entrenched a rigid caste hierarchy and other social divisions, was increasingly challenged by nationalist movements. The Indian National Congress, under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, was spearheading the fight for Indian independence. Gandhi, however, focused not only on political freedom but also on the social upliftment of the oppressed classes, particularly the Dalits.

Simultaneously, another important figure in the struggle for Dalit rights was Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, a leading social reformer and the architect of the Indian Constitution. Ambedkar, a Dalit himself, was concerned about the deep-rooted caste discrimination in Indian society and the political underrepresentation of the Dalit community.

He believed that for true political liberation to be achieved, Dalits needed to be politically empowered with separate representation in legislative bodies.

This growing conflict over the representation of Dalits came to a head in 1932 during the round-table conferences in London, which were aimed at resolving India’s constitutional issues. The British government proposed separate electorates for Dalits, which would allow them to elect their representatives independently of the general electorate. Gandhi, who was strongly opposed to this move, launched a fast-unto-death in Pune, arguing that separate electorates would further divide Indian society and entrench the caste system.

The Gandhi-Ambedkar Conflict

Gandhi’s opposition to separate electorates stemmed from his belief that separate representation for Dalits would deepen social divisions and perpetuate the feeling of untouchability. Gandhi’s idea was that the Indian society should be integrated, with Dalits (whom he referred to as Harijans or “children of God”) being absorbed into the general social fabric, and not isolated.

On the other hand, Dr. Ambedkar, who had witnessed firsthand the brutal discrimination faced by Dalits, believed that separate  electorates were essential to safeguard their political rights.

electorates were essential to safeguard their political rights.

He argued that without such a provision, Dalits would remain subjugated under the dominance of the higher castes in a united electorate. Ambedkar feared that Gandhi’s insistence on a common electorate would marginalize Dalits even further and prevent them from gaining political power.

This ideological clash between Gandhi and Ambedkar led to the famous Poona Pact.

The Poona Pact of 1932

On September 24, 1932, Gandhi’s fast-unto-death forced the British to intervene, and after negotiations, Gandhi and Ambedkar reached a compromise. The agreement, known as the Poona Pact, was signed in Poona (now Pune). The key points of the Poona Pact were:

- Joint Electorates with Reserved Seats: Instead of separate electorates for Dalits, the Poona Pact agreed on joint electorates, where Dalits would vote along with the rest of the population.

- However, there would be a provision for reserved seats for Dalits in these legislatures, ensuring their political representation. The number of reserved seats in provincial legislatures was fixed at 148 out of 493, and in the central legislature, it was 18 out of 250.

- Increased Representation for Dalits: The agreement also provided for an increased number of seats for Dalits, ensuring a stronger presence for them in the legislative bodies.

- Separate Representation in Local Bodies: In municipal and local bodies, Dalits would continue to have separate representation. This provision was seen as a step towards ensuring that Dalits would not be overwhelmed by the higher-caste population even at the local level.

- Veto Power for Dalits: One of the most important aspects of the Poona Pact was the provision of veto power for the Dalit representatives. In case of a dispute regarding the allocation of seats, the Dalit representatives could veto the decision.

Gandhi’s Role and Ambedkar’s Dilemma

Mahatma Gandhi’s decision to end his fast under these terms was a significant political move, though it came at a personal cost to him. Gandhi, in his efforts to bring unity to the Indian society, saw the Poona Pact as a temporary measure, hoping that over time, the separate identities of caste and untouchability would be eradicated.

For Ambedkar, signing the Poona Pact was a pragmatic decision. He had to balance his commitment to Dalit empowerment with the political reality of the time. Although Ambedkar was reluctant to give up on the idea of separate electorates, he knew that Gandhi’s popularity and influence made it impossible to win this battle at that point in time. The Poona Pact represented a compromise, though it did not fulfill all of Ambedkar’s demands.

While Gandhi’s idea of a joint electorate was accepted, it did not fully address the Dalit community’s deep desire for political autonomy. Ambedkar’s belief that Dalits should not be absorbed into a system that was inherently discriminatory remained unaddressed by the agreement. Nevertheless, the Poona Pact ensured that Dalits would have political representation and that their voice would be heard in legislative matters.

Aftermath of the Poona Pact

The Poona Pact had both positive and negative implications, and its aftermath is marked by both progress and limitations.

- Empowerment of Dalits through Representation: The most immediate positive outcome of the Poona Pact was the increased political representation for Dalits. The reserved seats in provincial and central legislatures allowed Dalit leaders to have a voice in national politics. This paved the way for further political and social reforms for the Dalit community, culminating in Dr. Ambedkar’s key role in the drafting of the Indian Constitution.

- Dr. Ambedkar’s Role in the Constitution: The Poona Pact and the representation it provided helped Ambedkar in his later role as the Chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Indian Constitution. Ambedkar was able to secure constitutional safeguards for the Dalit community, including the abolition of untouchability (Article 17), the provision of affirmative action (reservations in education, jobs, and legislatures), and the protection of the rights of marginalized communities.

- Long-term Impact on Caste-Based Politics: While the Poona Pact was a step forward in terms of political representation for Dalits, it also entrenched caste-based politics in India. The concept of separate electorates, though not fully implemented, continued to influence political discourse and policy-making in India. Over time, political parties began to cater to the caste-based demands of Dalits and other marginalized groups, leading to the rise of caste-based political parties and movements, particularly in states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

- Gandhi’s Legacy and the Harijan Movement: Gandhi’s role in the Poona Pact and his subsequent promotion of the Harijan movement (which sought to integrate Dalits into mainstream society) was important, but his vision of the abolition of untouchability was not fully realized. The belief that Dalits should be absorbed into the mainstream of Hindu society was seen by many as an insufficient solution to the problem of caste discrimination. Gandhi’s emphasis on non-violence and social reform was valuable, but it did not tackle the deeper economic and social inequalities faced by Dalits.

- Ambedkar’s Conversion to Buddhism: The Poona Pact did not resolve all of Ambedkar’s concerns, and his experiences with caste discrimination ultimately led him to abandon Hinduism. In 1956, Ambedkar converted to Buddhism, along with thousands of his followers, as a way to reject the caste system. His conversion marked a significant moment in Indian history, symbolizing the rejection of the Hindu social order and the search for an alternative spiritual path that offered equality and dignity.

- Legacy of the Poona Pact: The Poona Pact, while a compromise, laid the foundation for future struggles for social justice. It highlighted the need for a system that acknowledged the political rights of marginalized communities while grappling with the complexities of caste-based discrimination. The Poona Pact remains a key moment in the history of India’s struggle for democracy and equality, symbolizing the delicate balance between different political ideologies and the deep-rooted social structures that continue to define Indian society.

Conclusion

The Poona Pact of 1932 was a critical moment in India’s political history, bridging the ideological divide between Gandhi and Ambedkar on the issue of caste and untouchability. While it was a compromise that allowed Dalits to gain political representation, it did not fully address the deeper issues of caste-based discrimination.

The aftermath of the Poona Pact saw the continued struggle for Dalit rights, with Ambedkar’s vision of social and political equality continuing to inspire movements for justice and equality in India today. The Poona Pact thus represents both progress and limitations, highlighting the complexity of addressing caste-based inequality in a deeply divided society.

3. Religion and Spirituality

The book also explores the religious ideologies of both leaders. Gandhi’s adherence to Hinduism as a guiding moral and spiritual force is contrasted with Ambedkar’s eventual rejection of Hinduism, which he viewed as the foundation of caste oppression. Ambedkar’s conversion to Buddhism, along with millions of Dalits, is discussed as a revolutionary act of defiance against Gandhi’s Hindu reformism.

4. Economic Philosophy

Gandhi’s philosophy of trusteeship and his vision of a self-reliant, village-based economy are critiqued by Ambedkar, who saw them as regressive and impractical in addressing the socio-economic challenges of a modernizing India. Ambedkar favored industrialization and constitutional democracy as the means to achieve social equality and economic progress.

5. Political Leadership and Representation

Ambedkar’s emphasis on political representation for the oppressed is a recurring theme in the book. His demand for separate electorates and reservation for Dalits is discussed as a strategy to empower marginalized communities. In contrast, Gandhi’s reluctance to give political autonomy to Dalits is analyzed as a fundamental weakness in his leadership.

Ambedkar’s Vision of Social Justice

The book highlights Ambedkar’s unwavering commitment to social justice and equality. It argues that Ambedkar’s critique of Gandhi and Gandhism was not driven by personal animosity but by his larger vision of a just society. Ambedkar viewed Gandhi’s insistence on preserving the traditional Hindu social order as an obstacle to achieving true equality.

Ambedkar’s vision, as outlined in the book, was one of a society free from caste hierarchies, where individuals are treated as equals regardless of their birth. His insistence on constitutional safeguards and legal protections for Dalits is portrayed as a pragmatic approach to achieving long-term social transformation.

The Philosophical Divide

The book elaborates on the philosophical divide between the two leaders:

- Gandhi’s Idealism: Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence, Satyagraha, and spiritual morality is portrayed as rooted in traditional Hindu ethics. He believed in gradual reform and moral persuasion to bring about social change.

- Ambedkar’s Realism: Ambedkar, on the other hand, emphasized structural change and the need for institutional reforms. He believed that social justice could only be achieved through legal and political means, not moral appeals.

This fundamental difference in their worldviews underscores the enduring relevance of their debates.

Relevance in Contemporary Times

The book also touches upon the continuing relevance of Ambedkar’s critique of Gandhi and Gandhism in contemporary India. It argues that caste discrimination and inequality persist despite decades of constitutional safeguards and affirmative action. The authors suggest that Ambedkar’s ideas remain a guiding force for those fighting for social justice, while Gandhi’s vision of unity continues to inspire advocates of non-violence and harmony.

Impact of the Book

Ambedkar Ki Nazar Mein Gandhi Aur Gandhivaad is not just a historical analysis but also a call to critically examine the legacy of India’s freedom struggle. By presenting Ambedkar’s perspective on Gandhi, the book encourages readers to engage with the complexities of history and understand the challenges of creating an inclusive society.

It has sparked debates among scholars, activists, and policymakers about the relevance of Gandhi’s and Ambedkar’s ideas in addressing contemporary issues like caste discrimination, inequality, and social justice.

Why Read This Book?

- In-Depth Analysis: The book provides a detailed examination of the ideological differences between Ambedkar and Gandhi, offering insights into their thoughts and strategies.

- Historical Significance: It sheds light on key events like the Poona Pact and the debates surrounding caste and representation during the freedom struggle.

- Relevance Today: The book connects historical debates to contemporary issues, making it a valuable resource for understanding the challenges of caste and social justice in modern India.

- Balanced Perspective: While it primarily presents Ambedkar’s critique of Gandhi, it also acknowledges the contributions of both leaders to India’s socio-political landscape. ambedkar aur gandhi books

Conclusion

While the book provides a critical perspective on Gandhi and Gandhism, it also underscores the importance of engaging with differing viewpoints to understand the complexities of social change. Ambedkar Ki Nazar Mein Gandhi Aur Gandhivaad is a must-read for anyone seeking to delve deeper into the intellectual and ideological foundations of modern India. It offers a powerful reminder of the need to challenge entrenched inequalities and work towards a truly inclusive society.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.